From Scratch: Motor City Sewing

Paris. Milan. Detroit? Local menswear mavens, Sarah Lurtz and Sarah Lapinski (of Wound fashion designs) dream of turning their DIY sewing factory into Detroit’s premiere clothing manufacturer.From Scratch puts the spotlight on individuals and companies in SE Michigan that are building their businesses from the ground up. They are true pioneers in the new economy, reinventing the state’s identity and laying the foundation for Michigan’s future.

There is a momentary crisis at Motor City Sewing—the upstart sewing factory in the Russell Industrial Center. Scrutinizing a pair of military-style trousers, owners Sarah Lurtz and Sarah Lapinski (better known for their urban-dandy menswear line, Wound) are splitting hairs over a barely noticeable flaw in the stitching of the epaulette.

But no detail is too trivial in the clothing manufacturing business. Especially with plans as ambitious as theirs: to attract designers from across the Midwest, turning their new 800-square-foot factory into a manufacturing powerhouse.

“Everything has to be perfect,” Lurtz stresses. “There’s no room for flaw or inaccuracy.” She turns the cottony-soft fabric over in her hands, inspecting the back welt pockets, requiring a much more complicated stitch. “I don’t understand. These pockets are flawless, absolutely flawless.” She heads into the work room to discuss the problem with Jose—a skilled sewing hand they frequently pick up and take home from work.

“She’s such a good boss,” says Lapinski about her business partner, Lurtz, who is, by all measures, ultra-finicky but surprisingly patient. “We’re a family,” Lapinski adds. “We have to be.”

After all, this business is an experiment of sorts, and they’re all in it together. If it fails, the partners say, they’ll lose more than their jobs. The factory represents the last, best chance of getting their designs into production.

After all, this business is an experiment of sorts, and they’re all in it together. If it fails, the partners say, they’ll lose more than their jobs. The factory represents the last, best chance of getting their designs into production.

After a few bum scouting trips to LA last year, one soured factory relationship and another factory that dropped Wound for its itsy-bitsy production order, the duo decided to take matters into their own hands—literally.

“We knew we weren’t going to be able to get our stuff sewn otherwise,” says Lapinski. “Once [the factory in LA] realized how small we were, they didn’t want to touch it. Dealing with little people is infinitely more complicated.” Which is exactly why their business model makes so much sense: there’s a clear need.

Nothing like Motor City sewing exists in the Midwest. New York is too expensive. And LA —if you can find someone to take you on— is too far away to effectively manage quality control. “Finding production is the hardest thing… finding someone you trust,” Lapinski explains. As up-and-coming designers themselves, they understand what designers need from manufacturers: micro service, flawless execution, and reliability.

Of course, this insight comes from experience—and they wouldn’t be here, trying like zealots to spur new industry in Detroit, without struggling elsewhere first. “Initially, we thought, ‘Wow, we can draw a picture and have it magically turn into a pile of clothes,'” Lapinski says, laughing at their inexperience.

This is particularly funny, considering the backdrop of serious machinery that now overshadows their studio. Different colored can lamps bend over industrial Singer sewing machines, each one with a specific function —from surging edges to marking button holes. Gigantic rolls of fabric are piled under the custom-made cutting table, taking up half the room. There’s an industrial iron, a steam table, and a fabric cutter with a blade capable of cutting up to 2000 shirts at a time.

This is particularly funny, considering the backdrop of serious machinery that now overshadows their studio. Different colored can lamps bend over industrial Singer sewing machines, each one with a specific function —from surging edges to marking button holes. Gigantic rolls of fabric are piled under the custom-made cutting table, taking up half the room. There’s an industrial iron, a steam table, and a fabric cutter with a blade capable of cutting up to 2000 shirts at a time.

All this equipment and labor costs money —an area that has required remarkable creativity on their part. The factory is fueled by the marginal profits Wound generates (most notably, their irreverent line of artist-collaborative tees) and the duo’s second jobs as servers (Lapinski at Pegasus, Lurtz at Slows Bar-BQ). “We’re paying payroll out of our pockets right now—and out of tips,” Lapinski says. It’s hand to mouth, as they build their clientele.

Luckily, their vision is showing early signs of promise. Not yet finished with production of the pilot Wound line, Motor City Sewing has already accumulated a small roster of clients. In the works: samples for Cleveland designer Derek Hess and a small run for local designer Treas Charow, who recently piqued buyer interest with her womenswear line at the Las Vegas trade show, Magic. They’re manufacturing another small run of specialty denim for a Cleveland-based designer in exchange for six industrial sewing machines, and they’ll be handling the local Vivid Braille t-shirt line. “We have a definite, built-in clientele,” Lurtz says. “There’s a pretty strong and wide network of people in this business.”

What they don’t have, however, is a skilled workforce at the ready —which translates into additional funds (that they don’t have) for intensive training. To be clear: they haven’t yet opened the hiring nets, but when they do, they anticipate the need to train their staff from the ground up. “You’re not going to find many Americans who can work these machines,” Lapinski says.

It’s a circular conundrum. “We need employees, investors and clients—and they all seem to feed each other.” Which one comes first? Without a well-trained staff, it will be difficult to undertake significant orders—the golden ticket to profitability.

It’s a circular conundrum. “We need employees, investors and clients—and they all seem to feed each other.” Which one comes first? Without a well-trained staff, it will be difficult to undertake significant orders—the golden ticket to profitability.

“We need to tap into the Cool Initiatives stuff. We’re the ground up. Cool Cities…they don’t seem to have the proper infrastructure for understanding the needs and meeting the needs. Maybe a sewing manufacturing company isn’t that cool, but it’s connected to a lot of things that are glamorous and urban and exciting. And what really helps a city and the economy are its exports. We have to bring money in from the outside.”

So for now, Motor City sewing works in small batches, slowly building their business, focusing on quality over quantity. “We’re not trying to complete with China, and there are people —designers and boutiques— who understand that,” Lurtz says.

“It’s very important for people to support this,” says Julian, the talented right-hand-man the Sarahs met during their managerial tenure at the Pure Detroit Design Lab. Julian, who was working across the street at a shoe repair shop at the time, is a graduate of a five-year manufacturing course from Trinidad, where he also oversaw a clothing factory. A technical guru who “can make just about anything, it seems,” according to Lapinski, Julian is their lucky break.

Responsible for drafting patterns, prototypes and floor manager, he’s also the company sage, bringing a certain philosophical wisdom to the operation. “The city needs this,” he says.

And he’s right—in more ways than one. In a region notorious for its rusted beltway, new industry archetypes need to be embraced. If Detroit —and the Midwest, for that matter— wants to be a competitive force in the creative industries we’ve been hearing so much about, then both fashion designers as well as general consumers ought to be more discriminating about the source of their goods.

And he’s right—in more ways than one. In a region notorious for its rusted beltway, new industry archetypes need to be embraced. If Detroit —and the Midwest, for that matter— wants to be a competitive force in the creative industries we’ve been hearing so much about, then both fashion designers as well as general consumers ought to be more discriminating about the source of their goods.

Julian isn’t the only windfall from their two-year stint at the Design Lab —a retail incubator for local designers, many of whom will likely become clients one day. “What’s great is that we come from the same struggles of trying to be designers and trying to make it one-of-a-kind. We are them,” Lapinski says. “But to make fashion design a career, you have to have some kind of quantity and distribution.”

This from two designers who used to sew clothing by hand in a converted attic-studio. Lurtz and Lapinski are not abandoning their roots though. They’re applying the best parts of their DIY ideals to the tenets of mass production.

Now that’s innovation.

Meghan McEwen is a freelance writer…

Dave Krieger is Managing Photographer of Model D and major contributor to metromode

Photos:

Clothing in production

Julian sews clothing

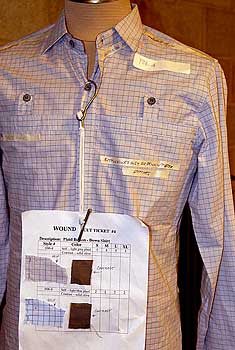

A shirt with modification notes

Sarah Lapinski and Sarah Lurtz

Spools of thread

Photographs © Dave Krieger